- Getting around Lijiang. Dont stay in the Old Towns more than 2 days, there is nothing to do. KRISS Oct 9, 2013 05:46

- 2013 Beijing Temple Fair BENNYLAU Feb 26, 2013 03:29

- Malaysian traveling from KUL - LAX vis Shanghai PVG ZATI_DY Jan 3, 2013 20:15

Taishan: From Bottom To Top

- Views: 5821

- |Vote: 0 0

- |Add to Favorites

- |Recommend to Friends

A Story of Creation

In the beginning, there was nothing but chaos and from this sprang a single egg. Inside the egg, Pan Gu (盘古) was growing, and he became so enormous that eventually he broke the egg. Some parts of the egg spiralled high to become the heavens and other parts of the egg sank and became the earth. Pan Gu thought this was beautiful, but he was frightened that somehow the earth and the sky would return to each other and so he put his body between them. For 18,000 years Pan Gu stood between the earth and the sky, continuing to grow and pushing them further and further apart until at last he was exhausted and fell asleep. He never woke again.

His eyes became the sun and the moon; his breath the wind; his voice the thunder; his blood the rivers; his veins the paths; his bones and teeth the stones and minerals; his flesh the soil and trees.

From his body sprang all the mountains and from his head: Taishan (泰山).

Mountain of Mountains

Of the famous five sacred mountains in China, Taishan boasts both a holy and culturally rich supremacy. It has been a site of homage and worship for around 3000 years, maintaining spiritual favour as a minion of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism.

Garnering vital political respect soon became intertwined with ascending Taishan, as legend dictated that heaven would surely never permit an unworthy ruler to reach the summit. Any who did therefore, were bestowed with divine approval.

Taishan has been scaled by as prestigious a list of pilgrims as any mountain could hope for. Emperors, scholars, academics, writers, poets, politicians and religious devotees have all come here seeking everything from divine intervention to divine inspiration. Quotations, poetry and inscriptions abound from such illustrious names as Emperor Qianlong, Confucius, Li Bai, Du Fu and Chairman Mao.

Such cultural and historical significance granted Taishan the honour of being the first UNESCO World Heritage Site in China (in 1987) with the hope that it might be preserved for all who wish to, to follow in the footsteps of the three millennia of pilgrims who passed before them.

…

Taishan remains the most popular and climbed of mountains in China. It is estimated to receive over 2 million visitors every year, which means on any one day you might be sharing the mountain with over 5000 other people. Not quite the spiritual climb you might wish for and a fact that has kept me away from this mountain for 2 years.

Nowadays urban mythology has it that if you climb Taishan and reach the summit you will live to be 100 years old (I'll let you know); and watching the sunrise from the summit is a must-do activity in the Shandong (山东) section of every respectable guide book about China – ancient Chinese lore having it that every morning, the sun begins its journey westwards from Taishan.

Meeting Taishan

This mixture of legend and fact lends a unique magnetism to Taishan and is responsible for finding me Shandong bound in the chilly depths of January to see if I too could make the grade. Every mountain throws down a gauntlet to those who wish to climb it and Taishan's may not be the most difficult logistically, but surely it has the most rich and splendid detail.

On the 25th January, me, some money, my camera and many layers of clothes get into a taxi. From the bus station in Tai'an (泰安) to the mountain itself is a short ride of less than 10 minutes and 10 RMB. It surprises me how invisible Taishan is from the town and the summit itself will remain hidden from my sight for almost the entire ascent. The weather is to blame; the cold heavy cloud has come to settle in for my winter climb. I am not unhappy about this, it holds in its hands the promise of something I am hoping to find at the top of the mountain: snow.

I am taking the central/middle path up the mountain, deeming it the most interesting and scenic route. I will descend via the western route for an alternative view of Taishan.

It is a 20-minute walk up through narrow stone-stepped streets edged with red walls, temples, steles, souvenir stalls, chickens and trees, until I reach the ticket booth. I pay the lady 80RMB, pass through the narrow turnstile, under the tunnel and I am ready to begin my trek up this fabled climb.

From The First Gate (一天门)

It is 12 noon as I begin and the temperature is around 10 degrees, I am already regretting all my layers of clothing and wondering how cold it can really be at the top. I am full of energy and excitement though and I'm sure I can feel the same anticipation for the summit as those who have gone before me and the cloud that obscures it only adds to the mystery.

This heady freedom carries me swiftly up these first stairs and through the muted browns and greys of the winter; the pine trees adding a respectful and quiet green to the gloomy skies. I am joined by chickens from time to time, but people are few and I climb alone feeling delighted for the unexpected peace that I've discovered here.

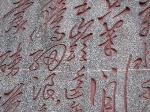

The path is initially flat, then climbs slightly with small staircases that increase in steepness. A number of temples lie scattered along the path, the steps of which take you through into the cloying scent of incense and out again. Inscriptions line the route on rocks and stones, it seems everyone has something to write about Taishan in beautiful calligraphy and ancient script. I feel history is keeping me company.

A man is descending the mountain wearing a woolly hat and fluorescent orange sleeveless top. He has a long pole resting over his right shoulder and on each end of the pole is a large bundle of neatly chopped branches. I move to the side to let his wide load pass – it looks heavy.

Beyond the path, the mountain exists as a layer of brown deadened grass studded with boulders and the trunks of trees. Sometimes I pass between woods of pines that seem as dusty and careworn as if they had been standing there through 3000 years of footsteps – they are probably the descendents of those that have. One, having given up, has collapsed its black trunk across the path to become part of the climb it has witnessed for so long.

A souvenir shop sells water from a tap, it is water from the mountain's springs (山泉). I realise I must have been climbing, it is colder here and the water around the tap is frozen in a big lump; apples and cucumbers are resting on a tray in a splash of red and green. The shop is made from wood and hung with carvings and natural branches, one resembling a dragon. (A woman charges me 1RMB here for taking a photograph of a chicken – in her defence, she points out a sign to me saying “1 photograph, 1 RMB” – in my defence, it is very small. The photograph is rubbish, but I keep it anyway as a reminder.)

Reaching the Middle Gate (中天门)

It takes me an hour and a half of walking to reach the Middle Gate. Here it is noticeably cooler and some of the rocks are covered in thick layers of ice. The last few hundred steps have been of a steeper gradient and have me puffing a little, lifting me into a wall of cloud through which cable cars swing silently.

Middle Gate is where the car park is located and tour buses must, I suppose, empty out their passengers onto the mountain. In the middle of winter it is deserted with just the odd car alone on the concrete. This is where many will start and finish their pilgrimage to Taishan.

The rock carvings and inscriptions increase and I feel as though I am walking through a cemetery. The poems and exclamations of the dead are like signatures of their lives. I pick a random inscription it is 峻岭 meaning lofty mountain, later research reveals it to be the simple thoughts of a member of the emperor's family in 1879.

I am hungry and take a welcome rest at a makeshift table and chairs. Lunch doesn't get any more delicious than a Shandong staple, a couple of freshly made pancakes with spring onion and a salty sauce (煎饼,豆瓣酱,大葱).

Beyond the Middle Gate

Here the climbing really begins. There are a few more people here, but it doesn't take long before I lose them in the ever-increasing number of steps. Ice appears amidst the trees like great white rocks and a cool wind rises, the zoom on my camera begins to stick and I am becoming glad of my down-filled jacket and thermals.

The impressive Wanzhang Stele or Lofty Stele (万丈碑) is visible from here. It is an inscription of the poem Chaoyang Cave (朝阳洞) written by Emperor Qianlong. The poem is carved onto a cliff face and appears tiny from where I am standing. It seems incredible that the stele stands 25 metres high and 13 metres wide and that each character is 1 metre wide.

I cross Cloud Walk Bridge (云步桥) and marvel at the waterfall that sits frozen beneath it. It is during the upward climb of a couple of hundred steps from here that I see the first snowflakes, rare as white gold, flicking through the air. They renew my energy, which is just as well, because Taishan saves the worst for last.

The Stairs to the Summit

The Path of 18 Bends (十八盘) is the steepest, most winding and densely stepped section of the climb that marks the final leg-breaking staircase to the South Gate to Heaven (南天门). I think the climb has been reasonable up until this point but the flat sections between the steps disappear and this is one long uphill slog. On a clear day it is possible to see the gate, but to me it just seems that I am making an endless climb into the clouds. There are snowflakes falling now with absentminded irregularity and I am refreshed at their light touch, hoping for a pristine snow-covered summit.

A few empty-tabled cafes cling to the edges of the steps at regular intervals. I inquire about the price of the cans of Red Bull sitting in vats of boiling water, it increases by approximately 2RMB per café as you ascend. As the cold deepens and my legs tire I take an irresistible stop for a hot Red Bull and some peanuts. The café owner tells me it is still a 30-minute climb to the top and that it might snow overnight. The temperature at the summit is -15°C. I sit and sip my drink, its warmth fizzes through me and I think that maybe I can fly – the café's scrawny cat wanders past and mews forlornly.

The sharp climb is at last taking its toll on my legs and I'm getting tired. At 1545 metres in height, Taishan is hardly the tallest mountain I've climbed, but this last grinding staircase zaps the energy in my legs. I have passed other people descending, but I walk, alone, to the summit and it requires the full determination of my mind to overcome the protest of my muscles.

It is some four and a half hours since I started my ascent of this mountain and the summit's promise of rest is welcome after the relentlessness of the stairs. When I reach the gate, a pair of thickly coated guards eye me coolly, and then smile. I smile back. I feel for a moment not only my own elation, but that of 3000 years of pilgrims who have stood here before me. I have reached the summit! I grin to myself and look down over the stairs, still panting but hugely satisfied: I feel worthy.

Copyright © 1998-2025 All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1998-2025 All rights reserved.