- Getting around Lijiang. Dont stay in the Old Towns more than 2 days, there is nothing to do. KRISS Oct 9, 2013 05:46

- 2013 Beijing Temple Fair BENNYLAU Feb 26, 2013 03:29

- Malaysian traveling from KUL - LAX vis Shanghai PVG ZATI_DY Jan 3, 2013 20:15

The River - Part Two - The Three Gorges

- Views: 7446

- |Vote: 0 0

- |Add to Favorites

- |Recommend to Friends

Blush of Dawn Cloud

The mist, the river, the colour of the sky, nothing had changed in the morning. I walked out on deck to see a gigantic Buddha arranged on a hillside, each part of the body made out of what appeared to be a white building, connected by a series of staircases up the mountain. A tourist attraction and religious shrine worked into a single architectural plan, it was one of those structures that symbolised the seamless marriage of the ancient and modern in China, evidence of which can be seen in China on a daily basis - the farmer speaking on his cellphone in the rice paddy. A spectacular artwork in the boat's lounge was a scene of the river and scraggy mountains towering above it; with its traditional flourishes and conservative watercolours, it could have been a thousand years old, save for the fact that the artist had thoughtfully inked in the steel communications tower on one of the highest peaks.

We were soon to reach the Three Gorges, and the ship was abuzz with something that approached excitement, in a lazy and very Chinese way. Infrequently, passengers would walk out to the nose of the ferry and quote an old poem about the Three Gorges, that I suspected had been a standard text at school. It had the ring of an incantation, a sliver of Chinese history that was a ticket to genuine participation in the spectacle we were about to see. I noticed several small groups of people in the lounge eating sunflower seeds and drinking goblets of sprite, and when one of their number went outside I had him write down the poem, by China's ancient bard Li Bai, 'Morning Departure from Baidi City' for me, making a mental note to attempt to understand it later, once my Chinese had progressed to the appropriate level. Chinese poetry is famously awful in translation in English, devoid of the subtleties that only Chinese characters can bear, but here is a humble rendition:

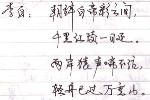

Leaving Baidi, cast in blush of dawn cloud

The day's passage to Jiangling a thousand miles

Monkeys cry incessantly from the river shores

This swift boat, already beyond these ten thousand mountains.

Li Bai

(The Original)

朝辞白帝彩云间

千里江陵一日还

两岸猿声啼不住

轻舟已过万重山

李白

Zhaoci Baidi cai yun jian

Qianli Jiangling yi ri huan

Liang an yuan sheng ti bu zhu

Qing zhou yi guo wan chong shan

Entering the Gorges

We were soon at the mouth of the first gorge. We were told that the further we passed through, the more lofty and impressive the gorges would appear. This was helpful, because in the dismal atmosphere of a downcast day on the Yangtze, the entrance to one of China's grandest natural wonders seemed exceedingly unremarkable. For those who aren't sure, a gorge is a narrow pass through a high-walled break in the land, and so I was half-expecting to be floating along the river-valley equivalent of the Grand Canyon. The Three Gorges, I discovered, are not immense cliff-faces after all, but in fact a tight series of mountains of increasing height through which the river passes. For me, at the time, this was a secret disappointment. For several hours we drifted through the gorges, each turn of the river offering views of other mountains rather like those just seen. I took a few photos and then gave up. I remembered having the same uncomfortable feeling when staring up at the peaks of Zhangjiajie, the excited and enthusiastic recommendations of foreigners and Chinese alike falling flat in the face of tall clods of rock.

I'm a city guy, I like back streets and old buildings and teenagers in weird clothes, I like being invited into people's homes and looking at their photographs, I like sitting around the table in a cafe or dining room listening to the things that interest real Chinese people: a mountain is a mountain, and despite the fact that I think that I should like going out into the countryside to look at them, I really don't. What was far more interesting was listening to the other passengers tell of their feelings at finally seeing this place, this location of Chinese legend soon to be yet another casualty of the river, soon what would hopefully be the last casualty of the river. With the river dammed and the gorges sunk, Those who live in the region may perhaps no longer live in the midst of an eternal, tired battle with the unpredictable surges of the Long River. One gentleman with whom I broached the subject was even more candid on the matter - "Look at them. They're not that spectacular. Chinese people from the rest of the country get excited about the gorges, those of us who live here know they're nothing special. I can't wait until the dam's finished, it'll make things a lot easier here."

Lu

Another foreigner had gotten on the boat in the morning, an English boy who had been travelling up and down the river for several days. Tim's Chinese was markedly better than ours, he was a student at Beijing University and someone who appeared to be in China for the right reasons. Many students of Chinese are just as self-important as the expats tend to be, assuming that their (often minor) abilities in Chinese entitle them to a status somewhat above native speakers, a confidence perhaps brought on by the astonishing encouragement given out by Chinese people to students of Mandarin. Chinese people are, almost without exception, surprised and delighted to hear a foreigner speak a few words of Chinese, and the ability is worth more than money in some situations. The students who take this praise too seriously become ugly participants in Chinese culture, and the blushing grin of a self-crowned lao wai in a Beijing nightclub is unmistakable, the gyrations of his majesty in the crowd of ordinary Chinese enough to make more humble foreign students almost want to choose another language, for fear of an association with, or worse becoming, something of the like. Tim chatted with us about his courses in Bei Da, perhaps the most prestigious Chinese school in the country, and about the abuse of cultural advantages (available along with the status of a fluent Chinese-speaking foreigner) often taken by some of the students there, often of a sexual nature. Tim was clearly far more interested in the Chinese language than he was in bad behaviour, and excitedly drew the latest character he'd mastered for us: 'lu', a pictogram of rain on the road, signifying exposure.

Our Nature

Outside, we watched the passing scenery of the gorges, dense fog lying on the river like a shroud. High on the slopes were markers indicating the maximum and minimum expected heights of the river after damming. It was surprising just how many constructions lay beneath the new water levels, old homes, pathways to hidden temples in the steep cliffs of some of the more treacherous mountainsides. I tried to gauge my own emotional reaction to the thought of these ancient places swallowed in the gray flood water, given that I had spoken with so many people with passionate views on the issue. Before coming to China, I'd only heard the side presented by the Western media, and hadn't anticipated the deep, emotional defense of the dam that local Chinese people would give. Like so many of the deeply anti-Chinese views often held by Westerners (regarding the government, Taiwan, Tibet, Tiananmen, and a host of other issues) it's difficult not to wonder at the arrogance with which Westerners presume to preach at Chinese people, whom they assume are brainwashed by their state-controlled media. It's difficult not to sympathise with Chinese who are tired of hearing Westerners all rant about the same tired issues, wondering who it is who's been brainwashing us.

Western propaganda too frequently casts the Chinese, and often the majority of the human race, as a force over and against nature. They do not allow for the perspectives of other cultures which try to find a more practical balance between long-term preservation and urgent human need. It's not that the Chinese disrespect the Three Gorges in any way, indeed the reverse is true. Its that the problems of the millions who live along the Yangtze’s shores need to be addressed regardless of the sacrifice this entails. Humanity is not a force against nature, we are come out from nature and are part of it, and have a determination for survival that is a legacy of our heritage as creatures of nature. The Chinese, and all peoples of the world, will lose the gorges as a result of this project, and for the mostpart they feel this loss acutely. But the needs that have moved the hearts of those involved in the project must take precedence over even ecological concerns.

The massive dam at the Three Gorges will certainly be built, despite the indignant condemnation of the project by foreign parties, and I didn't get the impression, sailing along the miserable Yangtze, that the loss would be as great as supposed. I certainly heard no symphony of monkey squeals resonating like bassoons or see any brilliant dawn clouds like Li Bai had all those centuries before when he wrote Morning Departure from Baidi City. I wasn't struck by the towering magnificence of the mounts or the glorious surge of the river. This is because the original majestic purity of the Three Gorges as it was in the time of Li Bai was long gone, and the industries and settlements along the river banks have long since become eyesores. In fact, it seemed to me that the civilisation along the river valley was rotten and wanting, that it would in some respects not be criminal after all to bury the place before the area's reputation as a shrine of deep Chinese cultural significance becomes even more spoilt and polluted. At least once these stocky blackened blocks are underwater, they will be able to command a respect in the mourning of them that they could not hope for on the sopping slopes.

Copyright © 1998-2026 All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1998-2026 All rights reserved.

1.

Feb 9, 2006 19:48 Reply

JABAROOTOO said:

Another good story

2.

Feb 9, 2006 19:47 Reply

JABAROOTOO said:

The huge white hillside sculpture is on Mingshan Mountain in Fengdu alias 'Ghost City' often the first stop for cruise boats downstream from Chongqing. The sculpture represents the 'King of Hell'