- Getting around Lijiang. Dont stay in the Old Towns more than 2 days, there is nothing to do. KRISS Oct 9, 2013 05:46

- 2013 Beijing Temple Fair BENNYLAU Feb 26, 2013 03:29

- Malaysian traveling from KUL - LAX vis Shanghai PVG ZATI_DY Jan 3, 2013 20:15

Ages Gone By in Shenyang

- Views: 6277

- |Vote: 1 0

- |Add to Favorites

- |Recommend to Friends

The Fathers of Shenyang

Shenyang has always had it hard. The weather is fiercely hot in summer and frighteningly cold in winter. The land is wide and rough, and the people have a correspondingly broad and hearty nature, the kind of culture that is born from tough lives and strong communities. Modern Shenyang is far more comfortable, but the feeling is still the same, and walking the streets of the city, you can sense the strength of the people in the air.

It should be remembered that this spirit of the Northeast once gave rise to the longest-lasting and most stable dynasty in Chinese history, ranging from 1644 until the collapse of the whole dynastic system in China almost a hundred years ago. It was in Shenyang, during the declining years of the Ming in the early 17th Century, that the Manchu powers collected themselves into a civilised force strong enough to defeat the decadent rule in Beijing and govern a unified country. It was a victory that would, in the long run, backfire, in that it would see the culture and independence of Manchuria fade away under the stronger and older Han traditions and language. The greatest legacy of this empire, perhaps, is the unifying concept of what it means to be Chinese, one that would encompass all of the minorities of the Empire and see its eventual transition into a nation.

In Shenyang’s Shenhe district, the Shenyang Imperial Palace Museum bears record to those early years of Qing history when the eight banners of the Manchurian tribes gathered together under the founder of their dynasty, the great Nurhaci. He was a born leader, at a time when the tribes of Manchuria were disorganised and engaged in constant squabbling, and it was he who finally brought them together – including the Mongolian speaking tribes of the region – under a military rule. Despite this, Nurhaci was more than just a martial chieftain, and his political abilities saw him go on to develop a successful civil administration in Beijing. He is thought to have been responsible for ensuring a writing system be developed for the Manchu language, which, had it not been reserved solely for the use of the Manchu minority, could have preserved his people’s language and culture. As it is, ethnically Manchu people today for the most part cannot speak their own language at all, and are effectively homogenised with the Han.

Nurhaci ordered the palace to be constructed in 1625, and it took eleven years to complete. It was clear that at that early stage, he already saw himself as a potential successor to the Ming, as his palace was based largely on the more well-known Forbidden City palace complex in Beijing. It’s smaller in scale to the palace in Beijing, however, and the architectural style and layout varies significantly. Wandering through the facilities, you will find that the Shenyang Palace is divided into three important sections, aligned along different axes, whereas the Beijing palace is strictly in a North-South orientation with the Emperor at the head. The Shenyang palace is a relic too of a combination of architectures – there’s the influence of the Han style as well as more Manchurian and Mongolian embellishments, an early indication of the inclusive outlook of the Qing dynasty. Most interestingly, the accommodation buildings are far taller than the throne rooms – it used to be said that Manchurian officials were always watching from their high windows even when sleeping!

Visiting the Palace

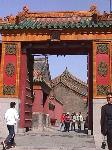

It costs 50 yuan to enter the Palace Museum – it’s easy to find, because the area around the palace has been decorated in the style of a traditional Chinese street – Shenhe is often called the Chinatown of Shenyang, with bright red lampposts, lanterns, and traditional wooden facades. Outwardly, the museum does look very similar to the Forbidden City in Beijing, surrounded by high red walls, with the traditional roofs of royal buildings visible over the top.

I went on a comfortably hot day in bright sunlight, and the interior of the palace was bathed in amber-red light. The initial sections directly through the front gate are a virtual maze, and I was initially overwhelmed by the number of exhibits – the whole complex has 300 rooms in 70 buildings. I was immediately attracted, however, by a group of women standing in stunning Manchurian clothing by an open door which advertised a traditional garments fashion show with an unusual twist. It was an extra few yuan, but I was intrigued and decided to check it out.

Inside, the room was dark, and very soon the model seemed to walk out on stage – I say seemed, because it wasn’t clear if she was really there or not – her clothes, through some trick of projection, kept changing – a whole series of exquisite Manchurian and Chinese designs. At one point her skin disappeared and we could only see her skeleton – some of the younger viewers emerged rather shaken!

I took a left turn and soon found myself in the most visually impressive part of the Palace, in front of the multi-levelled Phoenix Tower. Here, and in the buildings surrounding the great courtyard, was where the Emperor and his many beautiful concubines slept. They relaxed in an ornate tower called the Palace of Celestial Peace, and I reflected for a moment on just how celestially peaceful it would be to be an Emperor with so many beauties caring for you…

There are stairways and little pavilions throughout, and I took the chance to relax in a small pagoda by a stream running along the side of a steep marble wall, listening to the heavy traffic noise outside. Although not an Emperor, it was easy to feel how living in the palace really separated you from the common folk. Even today as a museum, it still has an atmosphere of luxuriousness, an air of class and peace.

The most spacious and historically significant section is the Eastern Way – where a short octagonal building stands before a grand series of ten pavilions, where the tribes of the Eight Banners would congregate for ceremonies and meetings. The building encloses a grand throne for the Emperor, and is called the Da Zheng Dian – the Hall of Great Affairs. I had a close look at the hall – there were some extraordinarily ornate decorations, both outside and in the throne room – and browsed the rack of Manchurian costumes laid out for tourists to put on – I watched as local Chinese travellers dressed themselves up and paraded around the very courtyard where their country’s history was made. Considering the freedoms China has won since that time, it didn’t seem inappropriate.

The East Tomb

The great Nurhaci is buried out to the east of Shenyang in a tomb that is far less ostentatious than the one constructed for his son in the north of the city, The tomb layout itself is, however, almost exactly the same. I took my sister to visit the tomb one afternoon, and when we later compared the photographs she’d taken with others I’d taken in the Northern Tomb, we found that the angles and views we’d chosen had been so similar it was almost impossible to tell which photo belonged to which tomb. The difference is that the approach to the Eastern Tomb is a long, straight pathway flanked by stone camels, horses and other animals, and this pathway terminates at a staircase of 108 stairs that leads all the way to the tomb entrance. Just as with the tomb of his son, walls and highly stylised period buildings are arranged around the courtyards in geomantically auspicious patterns. The design is very similar to that of the Imperial Palace itself, indicating that it was hoped the Emperor could continue to enjoy palacial surrounds in the afterworld.

Xi Ta

Shenyang has undergone various incarnations under various rulers – within the city can be found examples of Russian and Japanese architecture, as well as traditional Chinese, distinctively Manchurian, some Korean influences - and nowadays of course more modern international designs abound.

There are a few relics from the ancient past, including the Palace and the tombs, but interestingly enough four towers survive at the extremes of the old city wall of Tibetan design, tributes to the influence Tibetan Lamaism had exerted throughout China since the Yuan dynasty. The easiest of these towers to see (and they are reportedly all identical) is the Western Tower (Xi Ta) located in Xita District very close to the central Train Station. A white dagoba, like the one located in Beijing’s Beihai Park, it is decorated with guardian lions in high relief and crested with an ornate steeple with a crown of bells.

Sheli Tower

The oldest tower of all to be found in Shenyang is the Sheli Tower, dating from the Liao dynasty some 900 years ago. It’s located in a very cute warren of old-style homes in the North of Shenyang, and there is a small museum at the bottom. It’s 13 stories high, and although at the time I visited the tower it was closed off for climbing, it is reported that the view from the top affords a superb view of the ever changing skyline of Liaoning’s determined capital city.

Copyright © 1998-2026 All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1998-2026 All rights reserved.